Leanne Grabel

- Hole In The Head Review

- Oct 12, 2024

- 4 min read

Updated: Oct 31, 2024

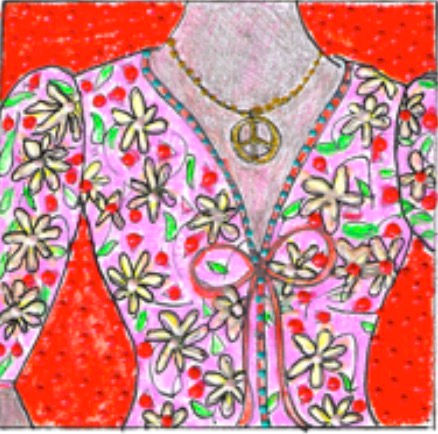

Stupid Blouse

Someone emailed me a poem by David Lehman.

I liked it and printed it.

I put it in my pocket.

There was a line about a piano:

Rank & file/Black & white.

I thought it was a good way to describe a piano.

Then I went to see my father.

He was asleep in his deathbed.

There was a tube down his throat.

It had a headlamp, a camera, and a sensor.

What was snorting down there?

Everyone was asking.

All the busy doctors were sifting through the membranes

caked with ash from cigar butts and steak fat.

He ate towers of salami, their casings stacked up like undershirts.

There were vats of anger.

Little sharp pellets of anguish.

And there was row of glass jars labeled Disappointments.

I went to see my father in my mother’s floral blouse.

It was probably crepe, so liquid.

Fit like a bath.

I knew my father would like it.

But I felt like a cupcake.

Or a cowgirl.

I sat on his deathbed and stared at the devastation.

Dry-eyed, lock-jawed, I put my hand on his arm.

His was mottled with blotches.

My hip touched his hip.

And I read him the poem by David Lehman.

He said he liked the piano. I knew he would.

And then his eyes closed and he slept.

I could see his life force leaking out with every breath.

Three days later, he died.

My mother was on Pacific Avenue heading to the cleaners.

She was picking up that stupid blouse.

I was on I-5 heading North picking up where I left off

Ugly Love Seat

I had no idea how hard my mother worked

to colorize her life

bleached by the disenchantments of my father

who blamed her for his failings.

What color was that, his disenchantment?

Olive green? Puce?

It was splashed over everything–

the easy chairs, the dinnerware, the comforters, us.

My father was no carpenter, no sculptor, no lover.

His vision for himself was impossible.

He wanted a throne, a crown, a scepter, a fleet.

His failure was inevitable.

He called my mother cunt at the dinner table.

This insured his failure to rise.

His mouth kept him scudding through dirt

chewing on pebbles of calcified ire.

For their final house, my mother got a new couch.

The decorator called the color mushroom bisque.

A fabulous name for such a weak brown, a dark beige.

I should have helped her.

I should have helped her choose a gem tone.

An emerald green or garnet red.

I should have shut my father up

then washed his mouth out with soap.

Thinking about Being Called Trite by a Poet

In the dark with the truth

I began the sentence of my life

and found it so simple there was no way

back into qualifying my thoughts

with irony or anything like that.

I went to the fridge and opened it

–William Stafford

She had on a mask when she said it to me.

I don’t know if she saw me hear her

or if my hearing her indeed was the intent.

I thought of the first time I heard her read.

She was wearing a mask with a thick Irish accent.

I understood very little.

We were on the same bill and I used a synthesized beat.

The audience seemed to love the beat.

But I saw her get angry, her eyes and forehead furrowed.

I wanted to tell her I try to entertain.

I try to use words that roll together like cue balls

quietly clacking along.

Is such soft joy stupid?

I’ve worked every day for it–

that and clarity.

Soft joy is the harder of the two

but clarity is no walk in the park.

And thick words are such a complication.

I want to tell the Irish poet that on Sundays

I actually take my brain off.

I wash it, kiss it and blow out the grunt.

On Sundays, I try just to feel.

And that Sunday, I felt we poets were being pathetic . . . again

avidly counting audience

hungry for a prize that won’t come

Wool

I was always small and fast.

I already told you.

I was in a big hurry from day one.

Once in kindergarten

walking back from recess

I decided to slip into the bathroom.

The teacher kept walking and

so did most the class.

Only a couple girls stayed behind.

I waved them in.

It was my first act of defiance.

Or was it resistance?

Our teacher was French.

She wore black wool cardigans

buttoned in the back.

There was something so French about her lips.

They were wavy and wry

lopsided, and gymnastic.

Only Shirley McCoy stayed with me in the bathroom.

We were there for a minute max, spinning with fear and thrill.

Then the teacher appeared and yelled us back into line.

We both had to stand in the corner when we got back.

I had to do twice as much time as Shirley, though

since it was my idea.

I think I only got in trouble three times throughout school.

This was the first time.

It made me feel strong and excited.

I kept giggling with little control.

I was always giggling with little control.

Laughter was all I had.

I don't remember getting in trouble when I got home.

My father admired defiance.

He probably gave me a dollar.

I do remember what I wore.

My favorite dress.

A red plaid A-line with a sewn-in dickey in light wool.

And there were about sixty tiny buttons

all the way down the back.

They were red and shiny like cherries, little cherries.

That was one problem with the dress, all that buttoning.

But the main problem was the light wool.

There was a very small window for wool in Stockton.

And I realize I’m not as courageous as I once was.

I may be more defiant, perhaps, but in a sour-breathed whisper.

The quietness, I suppose, cancels it all out.

Leanne Grabel is In love with mixing genres, Grabel’s newest work, Old With Jokes, a performance and chapbook, was created for ArtLab 2023. She was recipient of Bread & Roses Award in 2020.